We coudn’t care less

My decision to ride all three Mountain Race events came about in the simplest way possible. There was no grand planning, no mind maps, no clever tricks to postpone a decision I’d already made deep down. It was—like these things often are—pure coincidence. I ended up at a talk by Tomáš Fabián about the Tour Divide, where, at the very end, he hinted at his goals for the next year. One of them was the Silk Road Mountain Race in Kyrgyzstan.

That caught my attention. At the start of the year, there was no way I wanted to do anything like that. It seemed way too adventurous, too dangerous. If something went wrong out there, it could be a real mess. But a few months later, I went through this strange little transformation—maybe hitting the Christ’s age milestone had something to do with it—and I was suddenly ready to take the risk. So I told myself: I’m in too!

🐎 Why is the Silk Road Mountain Race so unique?

- It takes place at high altitude. The average is around three thousand meters, but the passes easily tip over four.

- The weather is wildly unpredictable. Down in the valleys, it can hit 40°C during the day, but at night up in the high passes it can drop to -15°C.

- Countless river crossings you can’t avoid. In the afternoon and evening, the current gets stronger, but in the morning the water is colder.

- In some places, rescue just isn’t an option. We were told straight up that even if you hit the SOS button, no helicopter’s coming. The organizer had two medical support cars on standby, but they can’t reach everywhere.

- The country’s bacterial spectrum—hygiene isn’t exactly a priority in Kyrgyzstan. Lots of riders end the race with stomach or digestive problems. Livestock is everywhere—so is their mess—and even in the mountains, the water isn’t clean.

- The safety situation is mixed. In some areas, embassies warn travelers to be extra careful. Alcohol is a real issue in the country—even though it’s majority Muslim. Once during the race, someone even got mugged… though in general, it should be OK.

- And then there are the “little things”: regular, intense thunderstorms, vast open landscapes with relentless wind and nowhere to hide, rockslides, barely any shops, no bike repair services, and so on.

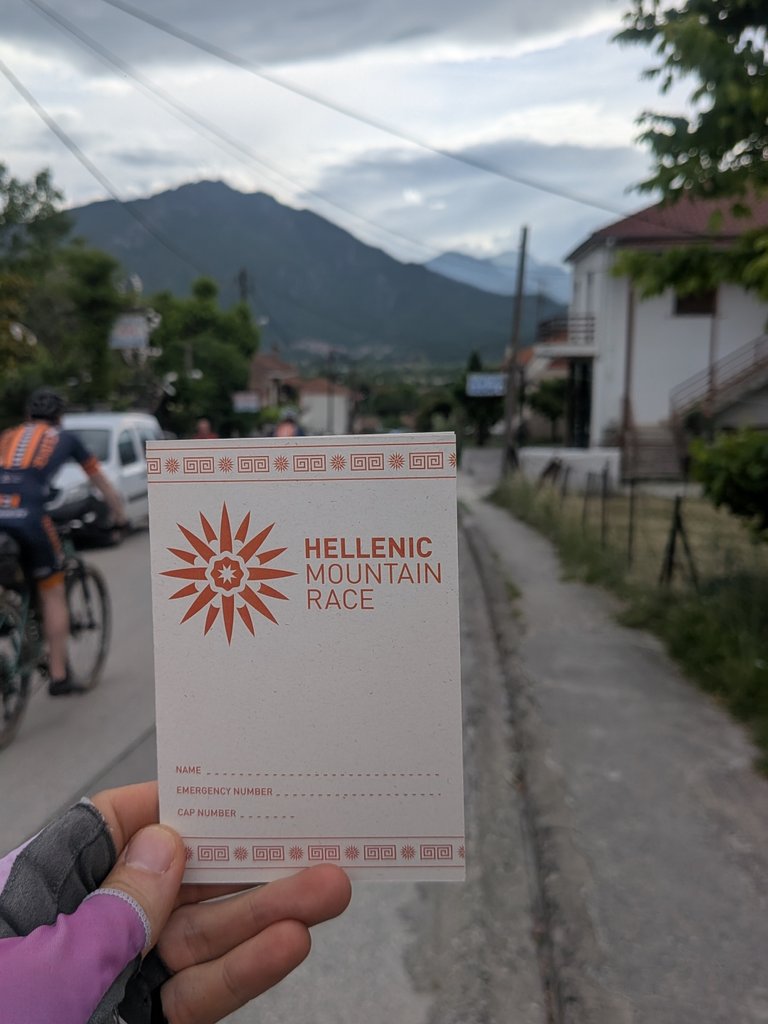

I was set on taking all of this on, but August was still far away. After closing the chapter of my steady 9-to-5 life, I wanted to experience something right away. I didn’t want to sit at home. I wanted adventure, and I wanted it soon. One of the earliest bikepacking races of the year is the Atlas Mountain Race, and I was lucky enough to get a spot. From there, the math was easy. One final race—the Hellenic Mountain Race—and I could complete the whole Triple. Logistically, it made perfect sense. I didn’t really overthink the execution.

The irony was that in this very year, I was heading into some of the world’s most prestigious races, but my hunger for racing was actually the lowest it had been in years. It wasn’t burnout or fatigue, just that my focus had shifted away from optimizing training loads. Honestly, I didn’t mind. I’m not chasing podium spots anyway. Heck, it’s hard enough to even find past results for these events. The point is the experience, and you don’t need peak form for that. Even so, I finished both the Atlas and the Hellenic in respectable times.

🍖 We Couldn’t Care Less

Since I’d already ditched the idea of structured training, I let myself ride from Greece back to Czechia by bike. It was a beautiful adventure, sure, but it also meant I didn’t have much time left to recover, let alone train properly. My power meter made that pretty clear. My numbers stayed flat all year long. The mileage I racked up was impressive, but mileage alone doesn’t cut it.

The race start was creeping—or rather sneaking—closer, and I still had no accommodation, no flight booked, hadn’t studied the route, and had no clue how this was all going to play out. From Czechia, there were supposed to be four of us: Tomáš Fabián, Tomáš Hadámek, Lukáš Klement, and me. Solid lineup. Lukáš was flying later—he’d been acclimatizing in an altitude tent—but the three of us wanted to get there early. Except the three of us couldn’t have cared less. We were all tied up with our own stuff, and the race was sliding into second place. Which is ridiculous, considering it was supposed to be the highlight of the season. It is the toughest MTB race in the world, after all! Our prep didn’t exactly reflect that. And yeah, it made everything harder later on.

A few days before departure, I cracked open the race manual again and started wondering what the hell I’d signed up for. The course description read like one brutal section after another. I began doubting myself. Even comments like “this is going to be the wildest edition yet” weren’t exactly soothing.

The race eventually reaches a remote valley hike that culminates with Suyek Pass (4020m). To get there

you will pass several old soviet bases either abandoned or in a serious state of disrepair before one final

military checkpoint just before leaving the Tar river which had a single border guard at the time of

scouting. From here it is one of the longest and hardest hikes that has ever been included in Silk Road

Mountain Race. In all it’s around 30 KM and will take many riders about a day to complete. It’s

essentially an animal track made by the herds and flocks of animals as they are brought up and down

this remote valley during the summer months…

🪿 Sleeping Bag, Please? Can I See It?

We managed to book flights for the same dates, so we all flew into Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second-largest city, together. Of course, I was still sorting out some gear at the last minute, and for a few items I couldn’t decide whether to bring them or not. I just tossed them into a box with my bike, planning to decide later.

Then, a few days before the flight, the organizers dropped a bomb: a sleeping bag rated for zero-degree comfort was now mandatory. Mine was rated 4, maybe 3 if I really pushed it, and everyone else wasn’t in much better shape. We were all relying on a combo of a lighter sleeping bag plus a down jacket and pants. We wisely requested special permission for this setup, which got approved. In the end, no one even checked it at the start…

Do you want to know what I brought to race? My complete gear list Silk Road Mountain race.

We flew to Kyrgyzstan ten days early, and our crew didn’t fully meet until Istanbul. Tomáš Hadámek was flying from Vienna, and we picked up a quasi-Czech—actually a German—Tony, a toy maker who cleverly spotted at the airport that we were planning this madness. I had only a vague idea how the transfer from the airport would work, or even where it would take us, since we had no accommodation booked. Luckily, the flight arrived at six in the morning, giving us plenty of time to figure it out.

At the airport, we ran into another Silk Road rider, Hanes from Switzerland, who had the misfortune of arriving in Osh without his bike. We were also worried our bikes might end up lost somewhere in Istanbul, but Hanes had a different problem: the Swiss precision timing failed, and his bike stayed behind in Zurich. Luckily, there was still enough time, and it arrived before the race started.

🚕 Airport Transfer

The entire plane’s contents were initially handled by a single immigration officer, so the line dragged on forever. Actually, it wasn’t really a line—more of a random cluster. Gradually, more Kyrgyz officials showed up at the counters, and finally we made it to the mini-airport area with a tiny currency exchange. My tactic was to swap soms for euros. But surprise, the teller didn’t like bills smaller than 50, so I didn’t get much local cash. Either way, I’d have to hit an ATM.

Getting a SIM card was more fun. I normally go for an eSIM because it’s simpler, but I’d heard local mobile plans were crazy cheap—probably a niche market. Unlimited calls, unlimited SMS, and unlimited data cost me about 5 EUR for a month. Unfortunately, in the chaos, I had shoved my old SIM into a money pouch, and at some point it spilled out. I lost my Czech SIM. Luckily, I didn’t need SMS verification; otherwise, I’d have been screwed. I had to embrace my new Kyrgyz identity, and anyone who wanted to reach me had to call my Kyrgyz number.

The local SIM turned out to be a great choice. Not only was it cheap, but data-only wouldn’t have been enough. Later, I had several calls in Russian, which was a challenge. Mostly I tried speaking very slowly and repeatedly in Czech, and sometimes it worked.

With the basics sorted, the transfer issue more or less solved itself. Immediately, a little crowd of eager folks with empty wallets surrounded us, sensing fresh exchanged cash. Some bikes ended up on the roof—not mine thankfully—secured with sheer willpower and a thin, almost invisible cord.

🦠 Tasting Osh

Our taxi stopped at a drive-through bakery. The bread the driver got, he poked and returned—it must’ve seemed too old. The seller then grabbed every loaf with bare hands, tested them all, and swapped it for one with the “right” quality. The driver shared it with us. If there was ever a time to get acquainted with the local bacterial landscape, it was now. I bit into the bread with gusto.

Osh was a full-on assault—especially for my lungs and sense of smell. The stench was incredible, though there were spots where it was even worse. European emission standards clearly didn’t exist here, and what came out of the exhausts defies my limited vocabulary.

Where did we end up in Osh? Tony had a hotel, so we thought we’d try there too. It was full, but a thought started forming—why a hotel at all? What we really needed was a warehouse for bike boxes and spare gear. And why stay put in Osh with this smell? We’d head straight into the mountains and start acclimatizing!

🦋 Butterfly Wings

It wasn’t that simple. The unlucky one of the day was Tomáš Hadámek. His bike had arrived, but not quite intact. During transport, a circular hole appeared and the spacer for the front axle fell out. A tiny piece of metal, but crucial … and hard to come by. Hope dies last, though, so he set off on a yellow electric scooter to hunt down the impossible across Osh’s streets, where asphalt was often a foreign concept.

It turned out to be a nice butterfly effect, because his experience later helped me directly in the race. If you search for a bike shop in Osh on Google Maps, you’ll get maybe three “relevant” results. Tomáš visited two of them and found nothing—or it was hidden. American-style online services don’t really work here. Here, it’s all about asking around. Sometimes the route is long, but eventually local knowledge will lead you to the right spot. After countless hours of questioning and phone calls, he managed to find a lathe and had the spacer custom-made.

🌍 Globus was a food heaven

Everything turned out fine in the end, so the four of us and four bikes were ready for an acclimatization ride. Just after dark, we were about to leave Osh. Before that, we made a quick stop at the local store—Globus—which would become a safe haven for our empty stomachs over the next few weeks.

Shopping here wasn’t bad at all. Besides huge piles of melons, many items could be bought by weight. Zero-waste enthusiasts would have been thrilled. You could buy not only the usual fruits and vegetables by weight, but also legumes, rice, dried fruit, nuts, spices, and even candies and cookies.

Tony also discovered jam in a pouch, another happy coincidence that later played a role in the race. The most common meal for me became bread with cheese. In Kyrgyzstan, “flat naan” is commonly sold, but unfortunately it was often hard and not very good. Only a few times did I manage to find a soft, perfect one that I happily munched on for a while.

Once we had everything loaded—and Tomáš Hadámek was still fixing a broken BOA strap—we could open the next chapter of our journey: the acclimatization ride.

Published | #Bikepacking

Silk Road Mountain Race 2025

- We coudn’t care less

- Acclimatization Ride

- Day #1 How I Was Asking For It

- Day #2 How I Caught the Snail

- Day #3 When It Rained Rocks

- Day #4 How I Crossed the Pamir Highway

- Day #5 How I Walked

- Day #6 How I became a sailboat

- Day #7 How I ate a meatless pizza with salami

- Day #8 How I almost froze

- Day #9 How I ate the fateful borscht

- Day #10 How I Was Surprised by Snow

- Day #11 How I Almost Swam

- Day #12 How Soldiers Stopped Me

💬 No comments yet

What are your thoughts? 🤔 Feel free to ask any questions 📫