Day #12 How Soldiers Stopped Me

The night at the bus stop wasn’t one of the better ones. My sleeping pad deflated during the night, but the tiles were still better than the cold ground. No one disturbed me and I didn’t even think about when the first bus would come. Traffic was minimal.

I had my alarm set for three thirty, but I couldn’t find the will to crawl out. It was cold and I was overwhelmed by thoughts - “Why should I even try”? The famous bikepacking race question “Why am I doing this?” hasn’t haunted me for a long time. It completely left me. Not that I’ve found the answer, but I’ve made peace with not needing to know everything. I know I’ll keep going, I just sometimes get hit with melancholy—why should I keep going fast. After all, there’s nothing at stake anymore…

The only challenge left tempting me was to reach the finish in daylight. When I delayed getting up, it was already clear it wouldn’t work out. I didn’t set the alarm for later, I just turned it off and lay back down. I didn’t leave my shelter until five thirty and soon regretted my decision.

I rode for a few more kilometers on beautiful asphalt when a strong wind hit me in the last village. I’d had just about enough. In my head I was already imagining being at the finish, but I still had over 220 kilometers to go. The wind was so strong I could barely move. It was like riding permanently uphill. I was afraid I wouldn’t make it to the finish that day.

🐑 Farewell to Kyrgyzstan

I cursed myself—I should have ridden all night yesterday, maybe it wouldn’t blow so much at night. Or if I’d left an hour earlier… But regret about the past wasn’t moving me forward. I kept hoping that around the next bend it would magically stop due to the airflow. It didn’t stop.

At one point I gave up. I needed to get water anyway and I saw a narrow stream. I stopped, sat down and started on the bread and cheese I’d bought at Globus yesterday. My favorite race combo. Soon a herd of cows came by. I thanked them for the cheese, even though they weren’t personally responsible for it. For a moment I felt such calm and peace, before I got back on the bike and battled the wind again.

I rode along the border river that separates Kyrgyzstan from Kazakhstan. I’d passed through several similar guarded border sections, but this was the first time they asked for my passport at the checkpoint.

As I climbed up in the national park, the wind gradually calmed down and my mind cleared.

Many areas in Kyrgyzstan were parched. Often no trees and clumps of dried grass or stones. It had its own charm. But this valley was different. An endless green carpet stretched all around and I passed through sheep herds several times, driven by local shepherds.

Even though I was feeling quite dejected when I woke up in the morning, here I thought to myself that this last section was a beautiful farewell to Kyrgyzstan.

At one point I met a young shepherd who stopped in front of me and gestured that he wanted money. I didn’t like that very much. I offered him a Snickers, which he accepted and in return gave me two apples. I think we were both happy with that trade. What could have been an unpleasant encounter turned into a nice moment.

🪖 Everyone Knows, Except Him

The first pass of the day was at 3,300 meters. The whole time a gentle slope rocked me along, though I felt in my legs that they didn’t have much strength or will to push through. Unfortunately I dropped my earphone tips somewhere, so I couldn’t finish listening to my audiobook, which I always rely on for the last day of a race.

I rode through another valley for several hours, but I couldn’t enjoy the scenery anymore. The sun was scorching hot, and since I didn’t put on sunscreen, I got pretty burned. I couldn’t take care of myself anymore. I just rode.

What was worst, in the middle of one climb I heard a whistle. At first I ignored it, but the whistling grew louder. A soldier was whistling at me and signaling for me to come to him. There was some kind of base there. He wanted my passport and a permit—which I didn’t have. According to the organizer, we had it specially arranged that they had the permits right at the border stations and we just showed our passports. The soldier, of course, knew nothing about this. I tried to argue with him through Google Translate—good thing I’d managed to install the Cyrillic keyboard. There was no signal there, of course, so I couldn’t even call anyone. But eventually he let me through, though he told me my efforts were futile and that they’d send me back at the next checkpoint. I had to ride up the hill again.

At the next checkpoint everything went smoothly. A quick flash of the passport was enough and I was heading to the last climb of the race at 3,800 meters. It was one of the easiest yet hardest climbs. The gradient was gentle everywhere, even broken asphalt at the bottom, but I was already so exhausted that it was pulling me down. I kept stopping, dragging myself along and couldn’t do it. I still managed to make one Chinese soup. Of course I didn’t have a stove with me, I just soaked it in cold water. It was sharp.

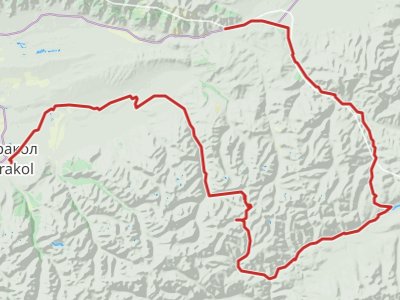

The final challenge of the race is a long loop around Karakol, the finishing point of the race. This is essentially the reverse of the start of the race route from 2023. We go around the finish line, along the Kazakh border to a wild and stunning valley, through the border checkpoint at Eshkilitash before doubling back towards Karakol via the old road to Enilcheck. This year we won’t go the whole way down to the ghost town near the abandoned tungsten mine, contenting ourselves with one final challenge: Chon Ashuu (3860m). We’ll then roll down to Karakol and the finish line. The

🌙 Under the Cover of Night

At the top, I reached the last pass at the moment of dusk. It was my luck because it was cooling down quickly. The finish was two thousand meters lower, so I put on everything except my down jacket and started the endless descent.

It took forever, but I didn’t have to exert myself much anymore. One car stopped, asking if I wanted a ride to Karakol. But I had to do this road myself. When I descended those two thousand meters of elevation, my tires lost some pressure. But I didn’t intend to stop and pump them up and preferred to risk riding on a softer suspension.

In the last flat section the wind blew at my back. Finally. But riding in Kyrgyzstan with cars was a pain. They blinded me, so I had to brake because I absolutely couldn’t see anything. When there was dirt piled across the road, I didn’t care and pushed on and on. They were probably just fixing something, but all prohibitions here are more like recommendations.

I’m writing this conclusion 4 months later, so I don’t remember exactly what was going through my head then. It doesn’t really matter. Because it’s always the same. Those who ride something like this for the first time expect something tremendous at the end. That something exceptional will happen at that finish. But it’s not like that. These races aren’t about what awaits you at the finish. It’s about your own journey. Nothing happens at the end.

I arrived at the gate marked Silk Road Mountain Race, where one volunteer greeted me. He gave me a stamp. He told me where I could find a hotel and where the 24-hour restaurant was. I felt like the race wasn’t ending. That I still had to deal with something.

First I went to the restaurant. I left my bike at the finish along with my clothes and I was a bit cold. I sat at a table and my spine rolled up like an accordion. I ordered pizza. Huge. Sometimes the door would open, from which dance music would always burst out, always waking me up for a moment. It was shortly after midnight and I’d had enough. I felt more sadness than joy.

😑 End of an Era

It took another 4 days for the “after party” to happen. It was a strange event for me. I’d been almost alone for almost two weeks. During the race I’d sporadically exchanged just a few words with someone and here most people were chasing their social deficit. They wanted to talk. But I still hadn’t recovered. I was still out there on those plains, in the mountains, alone with myself. Suddenly I was surrounded by people and didn’t know what to do with them. I couldn’t share my experiences when I hadn’t even had time to process them yet.

As one of the few, I took home a trophy. For completing all three races—the so-called Mountain Races Triple. Besides Silk, I also finished Atlas Mountain Race and Hellenic Mountain Race. I was glad I could take something physical away. Generally I’m not a fan of trophies, medals or T-shirts. Because they get old. When I finished my first 10-kilometer race, I was thrilled with the medal. When I ran a marathon, the 10-kilometer medal suddenly seemed pointless. I valued the first T-shirt from 1000 Miles, but when I have about 5 at home, they’re not as valuable. I have no idea if I’ll ever surpass this triple trophy.

And what was worst, when I left the after party, with my trophy in hand, and lay down in the yurt, it suddenly hit me that it was over. That this great adventure I’d been living for a whole year had suddenly ended. That was real sadness. All that remained was an uncertain future. I’d lost my goal. What’s next?

And how did the other Czechs do? Tomáš Hadámek finished about two days after me—he recovered from his intestinal problems. Tomáš Fabián unfortunately didn’t finish because he’d planned his timing too tightly and had to get to the airport. He didn’t make it through the last loop around Karakol and withdrew from fifth place. And me? I finished in 28th place in 11 days and 6 hours. It was my third longest race in terms of time.

Was all the suffering worth it? Did I regret it? Let me put it this way—I think everyone should experience something like this. But I can’t recommend it to anyone…

Published | #Bikepacking

Silk Road Mountain Race 2025

- We coudn’t care less

- Acclimatization Ride

- Day #1 How I Was Asking For It

- Day #2 How I Caught the Snail

- Day #3 When It Rained Rocks

- Day #4 How I Crossed the Pamir Highway

- Day #5 How I Walked

- Day #6 How I became a sailboat

- Day #7 How I ate a meatless pizza with salami

- Day #8 How I almost froze

- Day #9 How I ate the fateful borscht

- Day #10 How I Was Surprised by Snow

- Day #11 How I Almost Swam

- Day #12 How Soldiers Stopped Me

💬 No comments yet

What are your thoughts? 🤔 Feel free to ask any questions 📫